Contact: Michael Bernstein

415-978-3532, in San Francisco

September 10-13, 2006

202-872-4400 (Washington, D.C.)

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE: Thursday, Sept. 14, 3:00 p.m., Pacific Time

California scientists find natural way to control spread of destructive Argentine ants

SAN FRANCISCO, Sept. 14 - Pesticides haven't stopped them. Trapping hasn't worked, either. But now chemists and biologists at the University of California, Irvine, (UCI) think they may have found a natural way to finally check the spread of environmentally destructive Argentine ants in California and elsewhere in the United States: Spark a family feud.

The preliminary finding, by UCI organic chemist Kenneth Shea, evolutionary biologist Neil Tsutsui and graduate student Robert Sulc, was described today at the 232nd national meeting of the American Chemical Society, the world's largest scientific society.

Slight alterations in the "recognition" chemicals on the exoskeletons of these closely related pests, these scientists say, could transform "kissing cousins" into mortal enemies, triggering deadly in-fighting within their normally peaceful super colonies, which have numerous queens and can stretch hundreds of miles. One colony of Argentine ants is believed to extend almost the complete length of California, stretching from San Diego to Ukiah, 100 miles north of San Francisco. Their sheer numbers, cooperative behavior and lack of natural predators in the United States make these small, slender ants - only about 1/8 of an inch long - difficult to eradicate, Tsutsui and Shea say.

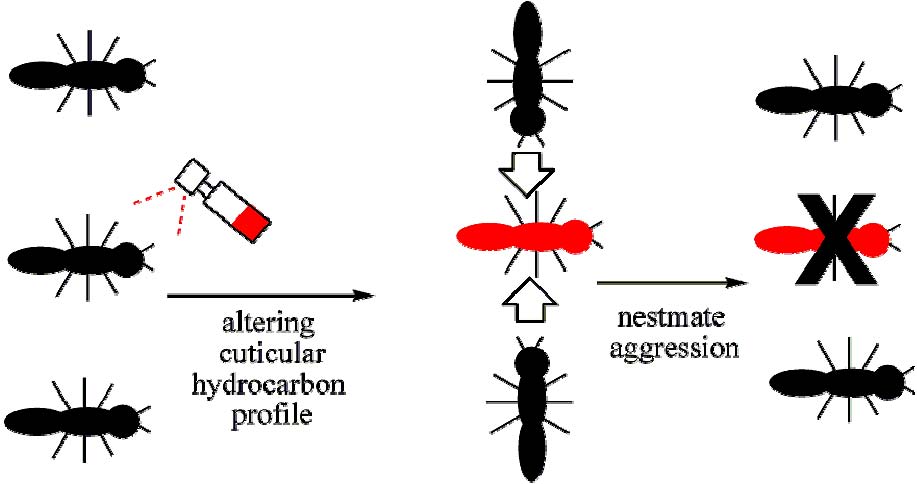

The ants use chemical cues on their exoskeletons to recognize other members of their colony. Because Argentine ants in the California super colony are so interrelated, they have similar "recognition" cues and generally cooperate with each other. But in their preliminary laboratory work, Shea and Tsutsui were able to create a slightly altered, synthetic version of one of these "recognition" compounds, which was composed mainly of linear hydrocarbons with one- to three-side chains called methyl groups. When coated onto experimental Argentine ants, the synthetic recognition compound caused untreated nest mates to attack.

"Our preliminary results strongly suggest that by manipulating these chemicals on the exoskeleton, one could disrupt the cooperative behavior of these ants and, in essence, trigger civil unrest within these huge colonies," Shea says. "Although further study is needed, this approach, if it proves successful, could enable us to better control this pest."

Argentine ants are one of the most widespread and ecologically damaging invasive species, Tsutsui said. When Argentine ants are introduced to a new habitat, they eliminate virtually all native species of ants. These effects ripple through the ecosystem, causing harm to species such as the imperiled Coastal Horned Lizard, which feeds exclusively on a few species of native ants. Argentine ants also cause significant harm to agricultural crops, such as citrus, by protecting aphids and scale insects from potential predators and parasites.

In their native South American habitat, Argentine ants are genetically diverse, have territories measured in yards rather than miles and are extremely aggressive toward encroaching colonies, literally tearing one another apart in battle, according to Tsutsui. But North American colonies are different. Because they are believed to be descended from a single small population of genetically similar ants, Argentine ants in United States essentially "recognize" each other as members of the same clan, he said.

"The final goal of this project would be to recognize the colony markers that distinguish one colony from another," Shea said. "Once we have an understanding of those markers, then it might be possible to use synthetic mixtures of hydrocarbons to either confuse or confound or otherwise disrupt social behavior."

Argentine ants were likely carried into the United States in the 1890s aboard cargo ships that docked in Louisiana. Although the proliferation of the ants has been slowed in the South and Southeast by the introduction of fire ants, Argentine ants are now the most common ant in California, Shea said.

The American Chemical Society - the world's largest scientific society - is a nonprofit organization chartered by the U.S. Congress and a global leader in providing access to chemistry-related research through its multiple databases, peer-reviewed journals and scientific conferences. Its main offices are in Washington, D.C., and Columbus, Ohio.

# # #

-Doug Dollemore

The paper on this research, AGRO 244, will be presented Thursday, Sept. 14, 3:10 p.m., at the San Francisco Marriott, Salon 2, during the symposium, "Characterizing Natural Products as Pesticides, Repellants, or Biomarkers."

Kenneth Shea, Ph.D., professor of chemistry, and Neil Tsutsui, Ph.D., assistant professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, are at the University of California, Irvine. Robert Sulc, a doctoral candidate at the university, presented the paper at the meeting.

ALL PAPERS ARE EMBARGOED UNTIL DATE AND TIME OF PRESENTATION, UNLESS OTHERWISE NOTED

The paper on this research, AGRO 244, will be presented at 12: AM, Thursday, 14 September 2006, during the symposium, "Characterizing Natural Products as Pesticides, Repellents, or Biomarkers".

AGRO 244

Synthesis and evaluation potential of nestmate recognition cues in the Argentine ant (Linepithema humile)

Program Selection: Division of Agrochemicals

Topic Selection: Characterizing Natural Products as Pesticides, Repellents, or Biomarkers

Lead Presenter's Email: rsulc@uci.edu

Robert Sulc1, Kenneth J. Shea1, Neil D. Tsutsui2, Miriam Brandt2, Candice W. Torres2, and Mikoyan Lagrimas2. (1) Department of Chemistry, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, CA 92697, rsulc@uci.edu, (2) Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, University of California, Irvine

Abstract

Nonnative species caused approximately $137 billion per year in ecological damage and loss in the United States. Among these foreign species is the Argentine ant, Linepithema humile, which is native in South America and has been introduced to Mediterranean climates worldwide. In its introduced range, intraspecific aggression is greatly reduced, colony boundaries are dissolved, and individuals mix freely among physically distinct nests leading to the formation of extensive supercolonies. To understand the mechanisms underlying this social structure, it is important to elucidate the nestmate recognition system in this species. In social insects, recognition cues are chemical in nature and contained in the lipid layer on the cuticle. In Argentine ants, the cuticular profile is composed mainly of linear hydrocarbon molecules of 33 or more carbons with at least one side chain methyl group. The goal of this research is to synthesize pure hydrocarbons believed to be responsible for nestmate recognition and test the effects on ant recognition. Linear hydrocarbons of 35-37 carbons with one to three methyl group side chains were synthesized. The ants were coated with known hydrocarbons identified as potential key elements in intercolony recognition (Figure 1). The ants' reactions were observed to a treated nestmate. While treatment with synthetic control alkanes did not cause an aggressive response, ants treated with synthetic versions of the candidate compounds were attacked by their nestmates. Identification of the essential hydrocarbons for nestmate recognition can permit control over aggression between nestmates by altering cuticular hydrocarbon profile. If successful, this could enable better control over this pest.

Researcher Provided Non-Technical Summary

Briefly explain in lay language what you have done, why it is significant and what are its implications (particularly to the general public) Argentine ants are a particularly widespread and damaging invasive species. Their invasive success arises primarily from their unusual social structure, in which extremely large "supercolonies" form across hundreds, or sometimes thousands, of kilometers. Argentine ants that belong to these supercolonies aggressively attack different species of ants as well as Argentine ants from other supercolonies. The chemical cues that allow Argentine ant workers to recognize the fellow members of their supercolonies are believed to be cuticular hydrocarbons (CHCs). In this study, we synthesized some of the CHCs present on the exoskeleton of Argentine ant workers, and tested them for the ability to alter how Argentine ants recognize each other. This work may help to elucidate the nestmate recognition system underlying the social structure in introduced populations, which is a crucial step in understanding the mechanisms of invasion in this pest species.

How new is this work and how does it differ from that of others who may be doing similar research? This work is still very new, in its preliminary stages. No papers have been submitted or published on this work yet, and the data collection and analysis are still in progress. Few other groups are performing work of this nature.

Special Instructions/feedback: The work presented here has not yet received any media coverage, as it has not near completion. Some of our prior work on Argentine ants has received a great deal of media coverage (listed above), but none of this coverage is related to the current work on CHCs.

Kenneth J. Shea

Department of Chemistry

University of California, Irvine

Irvine, CA 92697-2025

Phone Number: 949-824-5844

This information is available for reporters' use only.